One of the most iconic places has to be the Sydney Opera House. Its distinctive design has made it recognisable the world over, though, for such a beautiful and elegantly crafted space, it has quite the chequered history!

Location

In the early 1790s, the Aboriginal man Woollarawarre Bennelong – employed by the British as a cultural interlocutor (a person who takes part in a dialogue or conversation) – persuaded the then Governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, to build for him a brick hut on the Sydney peninsula point, giving it its colonial name: Bennelong Point. The land had belonged to the Aboriginals before being co-opted by the British. In December 1798, a half-moon battery was constructed at the extreme northern end of the Point, mounted with guns from HMAT Supply.

From 1818 to 1821, the tidal area between Bennelong Island and the mainland was filled with rocks excavated from Bennelong Point, and the entire area was levelled to create a low platform for the construction of Fort Macquarie. While the fort was being built, a large portion of the rocky escarpment at Bennelong Point was also cut away to allow a road to be built around the point from Sydney Cove to Farm Cove.

In the late 1950s – when the project to create the Sydney Opera House was first conceived – Bennelong Point became the prime site for construction, partly in tribute to its Aboriginal heritage and also to replace the now-disused Fort Macquarie Tram Depot that had previously claimed it as home.

Architecture

Designed by Danish architect Jørn Utzon, the Sydney Opera House was formally opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 20 October 1973, some 16 years after Utzon’s submission won the 1957 international design competition. Utzon’s design vision stood out to the Governor of New South Wales at the time, Premier Joseph Cahil, as being the ideal choice to firmly establish Sydney in the (Performing) Arts scene, and he authorised work to begin in 1958 with Utzon directing construction.

It soon became apparent, however, that the engineering required to realise the vision was far from straightforward, and from 1957 to 1963, the design team went through at least 12 iterations on the “form” of the Shells – or Sails, as they’re otherwise known – trying to find an economically acceptable solution (including schemes with parabolas, circular ribs and ellipsoids).

By 1963, Utzon and his team had come up with an elegant solution, however, by then, amid controversy – not to mention a change in the government of New South Wales; the elected Liberal, Robert Askin, a vocal critic of the project prior to gaining office – Utzon’s days were numbered.

The Opera House was eventually completed by an Australian architectural team headed by Peter Hall, and Utzon – who left Australia after being effectively forced to resign – never got to see the finished product.

It’s not a totally unhappy ending. Though Utzon never did return to Australia, he did agree, together with his son Jan Utzon, to create the long-term strategy that would see the Opera House flourish.

Construction

For a modest fee, one can book a tour that gives one the opportunity to follow an experienced guide around as they narrate many of the various aspects of what the public generally gets to see…and also some of those that aren’t typically on public view. These tours run regularly throughout the day, and each typically lasts about an hour.

What surprises most people – and certainly what surprised me – is that the famous Shells/Sails are actually constructed using several hundred thousand ceramic tiles. These tiles – which are self-cleaning and rarely ever get a scrub down by anything other than the elements – are complementary to the shape of the Shells/Sailes, which themselves provide optimum drainage. Utzon worked for almost three years with the Swedish company Höganäs on the development of the tiles, which are made from clay with a small percentage of crushed stone.

The composition of the tiles also eliminates glare; the surface of each tile is non-uniform, so sunlight refracts instead of directly reflecting back to the observer. That’s some pretty cool engineering behind a humble tile! 😎

Performance Venues

Much like the Pyramids of Egypt, the visual aesthetics of the Opera House are mainly external. The inside of the building being predominantly concrete and glass. Whilst this does have a certain beauty in its own right, arguably, the real beauty is within the performance venues themselves.

The various venues within the Opera House don’t incorporate the structure of the external building into their construction. This was something else that came as a surprise to me! Each venue is completely independent and exists as an isolated and self-contained space, with the walkways and halls within the Opera House connecting each.

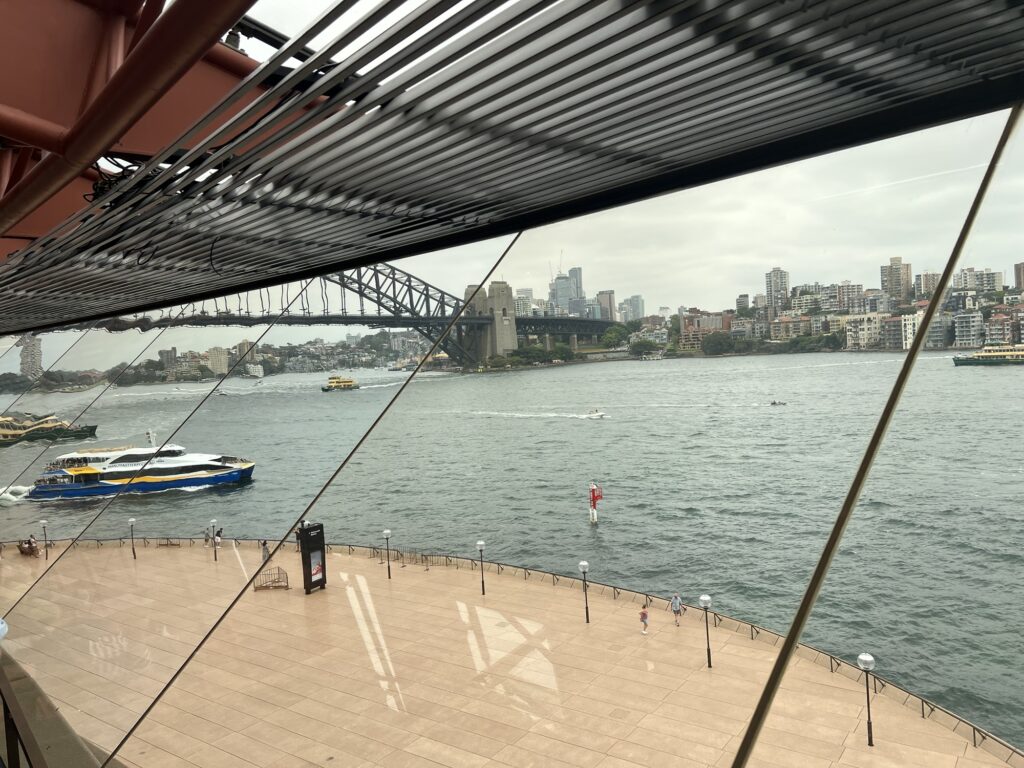

Each venue – of which the Concert Hall, the Drama Theatre and, of course, the Joan Southerland (the exterior of which is shown in the picture above) are the most known – essentially exists as a wooden “box”; think of them as buildings within buildings. The wood used depends on the venue’s use but is typically a mixture of (native) hardwoods and softwoods that together provide optimal acoustics.

Utzon Room

As a tribute to Jørn Utzon, one of the connecting spaces was repurposed and renamed the Utzon Room. This elegant and intimate venue seats just 200, has impeccable acoustics, and is adorned with a vibrant tapestry of Utzon’s own design. It is also unique in that it is a performance venue that incorporates the structure of the external building.

Visitors of Every Kind

If you’ve ever been to London then you may have visited the National Theatre (also referred to as the NT). Much like the Sydney Opera House, this sits alongside the waterfront – the River Thames – and is a Performing Arts venue visited by folks from far and wide. However, I don’t ever recall seeing anything quite like the floating behemoth pictured above parked outside of the NT! I’m not sure it would even fit down the Thames! 😳

Leave a Reply